Case report

A 34-year-old female patient (JG) was referred to the author for contact lens fitting in 1997. History revealed the patient to have undergone bilateral radial keratotomy (RK) approximately nine years earlier to reduce a relatively high degree (between 5 and 6 D) of myopia in both eyes. Unfortunately, the patient experienced a significant hyperopic shift in both eyes post-RK. In addition, the post surgical corneal contour was now markedly irregular, resulting in a decrease in the quality of vision experienced by the patient.

Further history revealed that the patient’s myopia had been diagnosed when she was seven years old at which time she was prescribed her first spectacle correction. JG had worn soft contact lenses (without problem) for about six years prior to her refractive surgery; there had been no contact lens wear subsequent to her RK. Presently JG was wearing a single vision spectacle prescription on a full-time basis. Her ocular history revealed no other notable findings. There was no significant familial ocular history. The general health of the patient was excellent and she was not on any medication.

Slit-lamp examination showed 16 equally spaced radial incisions in the mid-peripheral cornea of both eyes. The central 4 mm region of the corneae was relatively clear and minimal (<0.50 mm) corneal vascularization was noted. No other abnormalities were observed on ocular examination.

Corrected visual acuities were R 6/7.5+, L 6/7.5- (and N5 at near) with a manifest refraction of R +2.75/-0.50 x 10, L +3.25/-0.50 x 50.

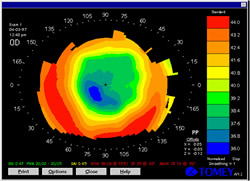

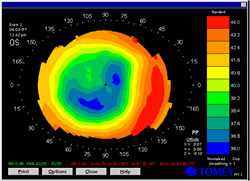

Videokeratoscopy with the TMS-2 (Computed Anatomy Inc., New York, NY, USA) revealed a corneal contour in both eyes that was relatively flat centrally and steep peripherally, hence similar to that of an oblate portion of an ellipse (Figures 1 and 2). [1,2] There was approximately seven diopters of central flattening in the right eye and about eight diopters of central flattening in the left (based on an estimated comparison between central and peripheral corneal curvature).

|

|

click to enlarge |

click to enlarge |

| Figure 1: Topographical map of the patient's right cornea. |

Figure 2: Topographical map of the patient's left cornea |

The ‘simulated keratometry’ readings obtained through videokeratoscopy were as follows:

| RE |

38.06 (8.87) @ 153 |

LE |

38.26 (8.82) @ 158 |

| |

37.35 (9.04) @ 63 |

|

36.61 (9.22) @ 68 |

|

Due to the markedly oblate corneae, the patient was prescribed a pair of spherical rigid gas permeable contact lenses incorporating a reverse geometry design. Unfortunately, even though the lenses were deemed to be a satisfactory fit on the eye and provided her with visual acuities of R and L 6/6, JG ceased wearing the rigid lenses after about 12 months due to persistent problems with lens discomfort.

JG returned to the author’s practice some years later in 2002 with the intention of resuming contact lens wear. Her corneal topography and spectacle refraction had not changed significantly over the past five years. Given her intolerance to rigid contact lens wear and the fact that silicone hydrogel lenses were now available, JG was subsequently refitted with disposable silicone hydrogel (Focus Night and Day) contact lenses incorporating the prescription R 8.6/13.8/+2.00, L 8.6/13.8/+2.50. With these lenses she was able to achieve visual acuities of R 6/6, L 6/6-. At the two week after-care appointment, no problems were noted with contact lens wear – JG was wearing the lenses 14 hours/day, 7 days/week – and slit-lamp examination revealed no abnormalities. She was duly advised to continue wearing these lenses on a daily wear basis with monthly lens replacement.

Discussion

RK is a surgical procedure that uses deep but non-penetrating radial corneal incisions to flatten the central radius of curvature so as to reduce the degree of myopia. It is not always completely successful, with a significant proportion of patients still required to wear some form of refractive correction after the procedure. Contact lenses are usually the preferred form of correction due to the irregular post-surgical corneal contour. Fitting contact lenses to a cornea that has undergone RK is generally quite difficult as the post-surgical corneal topography usually resembles the oblate portion of an ellipse. [3]

RK is less commonly performed these days due to the lower rates of surgical and optical complications achieved with other forms of refractive surgery such as photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) and laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK). The variability in refraction after RK is a major limitation of this procedure. The most notable finding from the Prospective Evaluation of Radial Keratotomy (PERK) study 10 years after surgery was the long-term instability of refractive error, with over 40% of eyes demonstrating a significant hyperopic shift post RK. [4] In addition, the corneal topography following RK may also change such that the degree of corneal astigmatism may increase and the corneal astigmatism may also become less regular.

Rigid contact lenses incorporating a reverse geometry design are generally a good option when fitting patients who have undergone RK. [5] These lenses will usually allow for appropriate alignment with the oblate cornea and provide the patient with optimal visual acuity. On the other hand, one could easily be forgiven for thinking that soft contact lenses represent a poor option for post-RK contact lens fitting. Soft lenses, even in toric form, do not neutralize the irregular corneal astigmatism which often occurs as a result of RK. Previously, there have been no soft lenses available in a reverse geometry design. Due to the oblate shape of the cornea, there can be negative fluid pressure between the conventional type of soft lens and the eye – causing the lens to become adherent to the cornea – which may result in an adverse physiological response to the lens. [5] There have also been reports of increased corneal stromal blood vessel growth following soft contact lens wear [6] as well as corneal vascularization along the incision lines. [7]

However, technological advances in soft lens material and design over the last ten years have resulted in many post-RK patients being fitted successfully with soft contact lenses. The introduction of silicone hydrogel lenses with their higher oxygen transmissibility (Dk/t between 60-180) has dramatically lessened the physiological concerns related to hypoxia and neovascularization. [8] In particular, the use of high Dk/t silicone hydrogel lenses on a daily wear basis has helped to minimize the incidence of incisional neovascularization. [3]

When fitting soft lenses to post-RK patients, it is generally best to err towards larger (flatter) base curves as flatter lens fits will tend to align more closely with the corneal contour and reduce the probability of corneal compression.9 There are also custom soft lens designs now available that incorporate a reverse geometry configuration to help reduce the excessive apical clearance that otherwise would normally be observed with a conventional soft lens design on an oblate cornea. An alternative to using a reverse geometry design would be to use a lens incorporating a silicone hydrogel material with a high modulus (such as the Focus Night and Day lens) and a flatter base curve (8.6), as was done for the patient in this case report. The use of the higher modulus (‘stiffer’) material will help to mask some of the irregular corneal astigmatism associated with the RK and it will also decrease the negative fluid pressure between the soft lens and the eye so that the likelihood of the lens becoming adherent to the cornea is diminished.

References

- Lindsay RG, Smith G, Atchison D. Descriptors of corneal shape. Optom Vis Sci 1998; 75: 156-158.

- Lindsay RG. Videokeratoscopy in contact lens practice. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2000; 23 (4): 128-134.

- Caroline PJ, Choo JD. Postrefractive surgery (Chapter 23). In Phillips AJ, Speedwell L eds. Contact Lenses 5th ed. London: Butterworth-Heinemann, London, 2006.

- Waring GO, Lynn MJ, McDonnell PJ. Results of the prospective evaluation of radial keratotomy (PERK) study 10 years after surgery. Arch Ophthalmol 1994; 112: 1298-1308.

- Lindsay RG. Contact lens fitting after radial keratotomy. Clin Exp Optom 2002; 85: 198-202.

- Shivitz IA, Arrowsmith PN, Russell BM. Contact lenses in the treatment of patients with over-corrected radial keratotomy. Ophthalmology 1987; 94: 899-903.

- Bores LD, Myers W, Cowden J. Radial keratotomy: An analysis of the American experience. Ann Ophthalmol 1981; 13: 941-948.

- Caroline PJ. Post-refractive surgery (Chapter 31). In Efron N, ed. Contact Lens Practice. London: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2002.

- Vickery J. Post RK and the soft lens. Contact Lens Forum 1986; 11: 34-35.

|