|

Contact lens associated keratitis

The cause or aetiology of the significant and serious keratitis responses to contact lens wear is varied, but has one common factor – the presence of micro-organisms. A small minority of contact lens associated-keratitis cases are potentially sight-threatening. Efron et al. recently calculated that up to 0.02% of contact lens wearers each year may lose two lines of best corrected visual acuity. [1] Schein et al. have reported a rate of 0.04% in extended wear of silicone hydrogels. [2]

Eye infections are rare because in most circumstances the ocular defence mechanisms which help resist infection are much superior to the ability of micro-organisms to invade the eye. In contact lens wear, the balance between bioburden (the number of micro-organisms at the ocular surface) and ocular defence is shifted significantly, and to avoid infection it is important that the increase in bioburden is minimised as much as possible. This increase in bioburden which occurs during contact lens wear can be affected by the hygiene and lens handling practices of a contact lens wearer.

Assessing current contact lens compliance

Webster’s Medical Dictionary defines ‘compliance’ as ‘the process of complying with a regimen of treatment’. [3] In the context of contact lens wear, this can be interpreted as a wearer correctly adhering to the instructions provided by the contact lens practitioner with respect to optimum lens wear and care.

Whilst many eyecare practitioners are familiar with the notion that many contact lens wearers are non-compliant, there is very little up-to-date objective data available to support this belief. In this report we present independent research which describes the lens wear and care habits of a large number of contact lens wearers across Europe.

Methodology

In the study, contact lens compliance was evaluated for 1,402 wearers of two-weekly or monthly-replaced lenses aged 16 – 64 years across seven European countries (UK, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Russia and Poland). This was a far-reaching web-based survey of contact lens use and covered areas such as the duration and frequency of contact lens wear, methods of lens cleaning and disinfection, the lens case and lens storage and the communications between lens wearer and contact lens practitioner.

On receipt of the study data a ‘traffic light’ approach was adopted to consider the compliance results. For each aspect of compliance, the responses of the subjects were categorised into:

- Green behaviour – a response considered to be wholly compliant with manufacturer guidelines and best contact lens clinical practice.

- Amber behaviour – a response considered to be moderately non-compliant. This category acknowledges that for some forms of contact lens misuse any associated risk is likely to be cumulative. For example, someone sleeping in daily wear contact lenses for one night per year is non-compliant but is at less risk of an associated adverse event than another person sleeping in daily wear contact lenses most nights. This categorisation acknowledges, therefore, that there are different levels of non-compliance in contact lens wear. However, amber behaviour should still be recognised as being clinically undesirable and only green behaviour should be promoted to contact lens wearers.

- Red behaviour – a response considered to be very non-compliant.

Table 1 shows the compliance questions in the survey and how the various answers were categorised. Most questions were asked to both daily wearers and extended wearers; some questions were specific to the wearer groups.

Group |

Question |

Green response |

Amber response |

Red response |

Both |

How many days do you wear your lenses before throwing them out? |

As recommended for lens type |

Up to 10% extra |

More than 10% extra |

DW only |

Do you sleep overnight in your lenses? |

Never sleeping overnight in lenses |

Sleeping overnight in lenses, but less often than once a month |

Sleeping in lenses overnight at least once a month |

DW only |

Do you nap in your lenses? |

Never |

n/a |

Some napping |

EW only |

How often do you sleep in your lenses? |

As advised by practitioner or less |

n/a |

More than advised |

Both |

Do you wash your hands before inserting and removing, and what with? |

Always wash hands with soap, antiseptic liquid, or wipes |

Always washing hands with at least water |

Not always washing hands |

Both |

What do you use to clean/store your contact lenses? |

Multipurpose / Hydrogen Peroxide |

n/a |

Saline only / any water or saliva / cleanser-protein only |

Both |

Where do you store your contact lenses? |

In a lens case |

n/a |

In a mug/glass |

Both |

Do you replace your solution or top up? |

Always replacing all solutions in the lens case |

n/a |

At least sometimes topping up |

Both |

Do you cover your contact lens completely? |

Always |

n/a |

Less frequently |

Both |

Do you close your lens case tightly? |

Always |

n/a |

Less frequently |

Both |

Do you clean your case? |

Every day with solution |

At least once a week with solution |

Without solution or less often than once a week |

Both |

How often do you change your case? |

Monthly |

Every 3-4 months |

Anything worse |

Both |

Do you close the cap of your bottle tightly |

Yes - always |

n/a |

Anything worse |

Both |

Do you ever check the expiry date of your solution bottle? |

Yes – regularly |

Yes – occasionally |

Less frequently |

Both |

Do you ever share your contact lens case with other people? |

Never |

n/a |

At least sometimes |

| Table 1: Key compliance measures. DW = daily wear group; EW = extended wear group. |

Results

For the purpose of this study, the various steps of lens wear and care across all the respondents were considered to have ‘high’, ‘moderate’ and ‘poor’ levels of compliance if correctly carried out by over 80%, 40%-80% and below 40% of respondents, respectively.

Only 0.3% of wearers were fully compliant for all 14 steps required for correct daily wear compared with 2.7% of extended wearers.

|

Behaviour of daily wear group |

Behaviour of extended wear group |

High level of compliance |

Using the correct solution

Lenses stored in a lens case

Lenses covered with solution during disinfecting

Case lid closed tightly

Bottle cap closed tightly

Case not shared |

Using the correct solution

Lenses stored in a lens case

Lenses covered with solution during disinfecting

Case lid closed tightly

Bottle cap closed tightly

Case not shared |

Moderate level of compliance |

Too many days of wear

Overnight wear with lenses prescribed for daily wear only

Correct hand-washing

Replacement of all solution each day (i.e. no topping up) |

Too many days of wear

Too many nights sleeping in lenses

Correct hand-washing

Replacement of all solution each time (i.e. no topping up)

Regular checking of expiry dates |

Low level of compliance |

Napping with lenses

Monthly replacement of lens case

Always cleaning lens case

Regular checking of expiry dates |

Monthly replacement of lens case

Always cleaning lens case |

| Table 2: Summary of compliance of daily wear and extended wear respondents. |

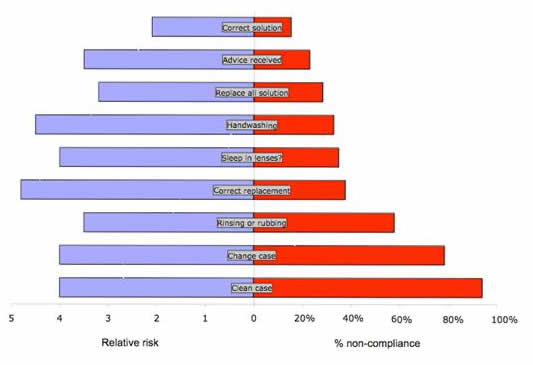

Figure 1 represents a number of compliance and other factors with a corresponding relative risk in each case. This allows a judgement to be made about the areas of lens care which should receive specific attention.

Figure 1: Relative risks and non-compliance for a range of compliance and usage factors.

Data for use of correct solution and unscheduled sleeping in lens from Radford et al. (1998) for microbial keratitis. [8] Data for receipt of advice and lens cleaning from Radford et al. (1995) for Acanthamoeba keratitis. [9] Data for replacing all solution and handwashing from Stapleton et al. (2007) for Fusarium keratitis and microbial keratitis, respectively. [10] Data for correct lens replacement from Saw et al. (2007) for Fusarium keratitis. [4] Data for case care from Houang (2001) for microbial keratitis. [11] |

|

Improper case care has been associated with an increased risk of infection [4] and it is apparent from Figure 1 that care of the lens case is frequently inadequate. Surveys have reported that up to 77% of lens cases are contaminated with bacteria and 8% with Acanthamoeba. [5] Contamination appears to be unrelated to solution type, and it is clear that the development of microbial biofilms in contact lens cases can reduce the effect of a disinfecting solution. [6]

We found that handwashing was actually performed well by the majority of wearers; however, as this function has been associated with a significant increase in risk of infection, it merits some consideration. Three quarters of the ‘hand washers’ used soap, 14% used just water with the remainder using antiseptic liquid or wet wipes. Research suggests that ‘normal’ liquid soap and antimicrobial liquid soap perform similarly in a typical population in terms of their ability to remove bacteria from the hands. Evidence from the use of hand washes in hospitals confirms that an element of training in the best methods of hand washing is required, [7] and it would seem reasonable to assume that this would be helpful to contact lens wearers also.

Sleeping in lenses was reported by about one third of daily wearers; unscheduled overnight use was reported by Radford et al. as being associated with a four-fold increased in the risk for microbial keratitis. [8] It is important that any such use of lenses by a wearer is known to their contact lens practitioner so that the most suitable lenses are prescribed; in this case, silicone hydrogels would likely be the lens of choice because although the incidence of significant or serious keratitis has been shown to be similar for silicone hydrogel extended wear and conventional hydrogel extended wear, the severity of such an adverse event is lower when silicone hydrogels are worn. [1]

Using lenses beyond their recommended replacement schedule has been associated with an increase in infections in a recently-published report from Singapore. [4] The increased risk in this form of non-compliance may vary with different lens materials and would presumably be related to the degree of non-compliance, but a four-fold risk compared with appropriately discarded lenses is clearly significant.

Understanding the risks of non-compliance

In the main, contact lens wearers understood that they were more likely to be at an increased risk of having an eye infection due to their lens wear, with 69% of wearers suggesting at least a slightly higher risk for contact lens wearers. Importantly, it was confirmed that in general contact lens wearers know that not following their recommended lens care regime increases the risk of an eye infection. This suggests that there is an inherent understanding by contact lens wearers of the importance of adhering to the messages conveyed by their contact lens practitioner which, in turn, indicates that any attempts by practitioners to improve their communication should result in better compliance by contact lens wearers.

Lessons for practitioners

Historically, contact lens follow-up aftercare visits have focussed on the performance of contact lenses on the eye and an examination of the ocular surface to check for any contact lens-induced changes. Whilst these clinical techniques remain important, a balance must also be struck with careful discussion and questioning of a contact lens wearer to determine his or her level of compliance.

The evidence linking inappropriate use of contact lenses and their care systems with increased risk of ocular infection is strong and it is imperative that contact lens practitioners consider potential non-compliance of their wearers at both the dispensing of new contact lenses and at follow-up aftercare visits. Wearers should be questioned on the use of their contact lenses, care products and in particular, the use of their lens case. If these aspects of compliance are enhanced, then the risk of a corneal infection during contact lens wear will be diminished.

Conclusions

This research confirms that the very basic aspects of lens care – using a solution for lens storage, closing lids and caps on cases and bottles and not sharing contact lens products – are usually correctly performed by contact lens wearers. We confirm, however, that many wearers like to stretch the use of their contact lens products by using lenses for too many days, sleeping in lenses when daily wear use only has been prescribed, sleeping in lenses for too many nights in the case of extended wear, and topping-up solutions rather than discarding each time. Significantly, only a minority of wearers care for their contact lens case correctly, and as this is a known risk factor for ocular infection, the need for much improved use of contact lens cases is a key message from this study.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an educational grant from Bausch & Lomb Inc.

References

Efron N, Morgan PB, Hill EA, Raynor MK, Tullo AB. Incidence and morbidity of hospital-presenting corneal infiltrative events associated with contact lens wear. Clin Exp Optom 2005;88:232-9.

- Schein OD, McNally JJ, Katz J, et al. The incidence of microbial keratitis among wearers of a 30-day silicone hydrogel extended-wear contact lens. Ophthalmology 2005;112:2172-9.

- Merriam-Webster's Medical Dictionary.

- Saw SM, Ooi PL, Tan DT, et al. Risk factors for contact lens-related fusarium keratitis: a case-control study in Singapore. Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125:611-7.

- Gray TB, Cursons RTM, Sherwan JF, Rose PR. Acanthamoeba, bacterial, and fungal contamination of lens storage cases. Br J Ophthalmol 1995;79:601-605.

- McLaughlin-Borlace L, Stapleton F, Matheson M, Dart JK. Bacterial biofilm on contact lenses and lens storage cases in wearers with microbial keratitis. J Appl Microbiol 1998;84:827-38.

- Larson E, Aiello A, Lee LV, Della-Latta P, Gomez-Duarte C, Lin S. Short- and long-term effects of handwashing with antimicrobial or plain soap in the community. J Community Health 2003;28:139-50.

- Radford CF, Minassian DC, Dart JK. Disposable contact lens use as a risk factor for microbial keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol 1998;82:1272-1275.

- Radford CF, Bacon AS, Dart JKG, Minassian DC. Risk factors for Acanthamoeba keratitis in contact lens users: a case control study. Brit Med J 1995;310:1567-1570.

- Stapleton F, Keay L, Jalbert I, Cole N. The epidemiology of contact lens related infiltrates. Optom Vis Sci 2007;84:257-72.

- Houang E, Lam D, Fan D, Seal D. Microbial keratitis in Hong Kong: relationship to climate, environment and contact-lens disinfection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2001;95:361-7.

|